Share This Article

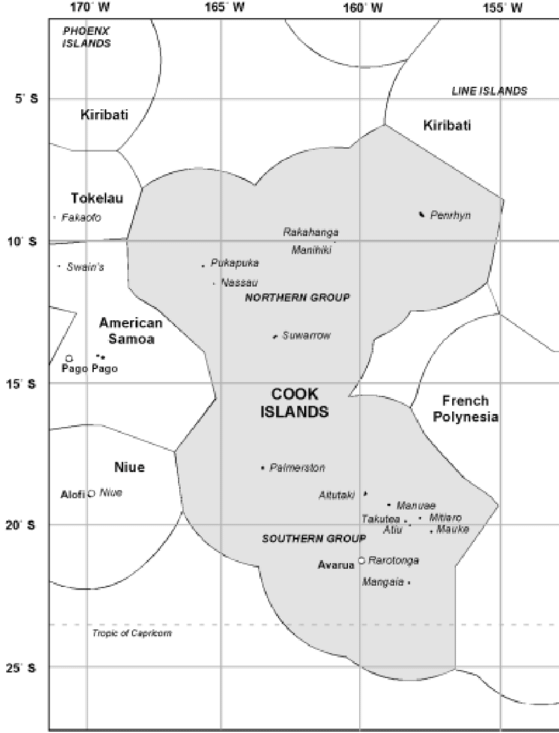

3000km northeast of Auckland, the Cook Islands are a collection of tiny dots in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The largest of these dots is Rarotonga—a perfect place to escape Sydney between semesters.

And yet, just days after arriving in Raro, I found myself seated in the courtroom of the Ministry of Justice watching the law unfold on this small island. There was no turning back. My intended break from university had transformed into a reflection on my studies to date, and the application of law in an exciting, diverse context. This article will examine aspects of criminal law, public law, torts, contracts, and international law in the Cook Islands. Although I haven’t studied property law, it would be remiss of me not to also mention the significance of land law to Cook Islanders.

Criminal Law

Even island paradises need a criminal justice system to mark the line between right and wrong, and punitive measures to deal with convicted offenders.

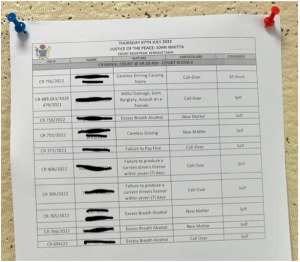

In the Cook Islands Ministry of Justice, the criminal court sits on Thursdays. An A4 sheet is pinned on a noticeboard outside the courtroom listing all the matters for the day to be heard by a Justice of the Peace. For serious offences, trial by jury is either mandatory or elected by either the prosecution or the defence.

Acts or omissions that are criminal offences in the Cook Islands are set out by the Crimes Act 1969. This Act has thirteen parts including crimes against public order; the person; reputation; the rights of property; religion, morality, and public welfare. The Act also includes crimes affecting the administration of justice such as bribery and corruption.

On my first night on Raro, a drug kingpin named ‘Oz’ was arrested for assault just a few doors down from our accommodation. Under the dangerous influence of ‘P’ (meth), Oz was transported to the local medical centre before being sent to the island jail. Under the Cook Islands Constitution, Oz is guaranteed general trial fairness and the presumption of innocence. However, there are some notable absences in criminal procedure legislation. There is no requirement for his trial to take place within a reasonable time; no right to be provided legal assistance; and no mention of the principle of double jeopardy.

On my second day at the court, I was fortunate to meet a local criminal defence lawyer who highlighted the importance of using community healing to achieve restorative justice for victims of crime in the Cook Islands. By showing the court how an offender has apologised to a victim’s family (and offering them some form of reparation) the severity of sentences can be reduced. It is interesting that, at the time of writing, the Minister for Corrective Services in the Cook Islands cabinet is also the Minister for Cultural Development.

Criminal law in the Cook Islands is not free from controversy. Under section 154 of the Crimes Act 1969, ‘indecency’ between males attracts a maximum sentence of five years imprisonment. This means that two men can be sent to prison for engaging in sexual activities, even if they both consented. There is no complementary offence for ‘indecency’ between women. The criminalisation of male homosexuality is a significant issue for Cook Islanders. All along the main road of Raro, people use signs and flags to either support or protest the repeal of the offence.

Also of note is the Narcotics and Misuse of Drugs Act 2004 which, among other things, prohibits the dealing of cannabis in the Cook Islands. On 1 August 2022, Cook Islanders voted in a non-binding referendum asking, “Should we review our cannabis laws to allow for research and medicinal use?” 62% voted yes.

Public Law

The Cook Islands has a representative democracy within a constitutional monarchy. This means that the King of New Zealand is the Head of State (represented in Rarotonga by the King’s Representative) and the Prime Minister is the Head of Government. In August 2022, the Cook Islands Party won the national election and continues to govern the country under the leadership of Prime Minister Mark Brown.

Public powers are limited and controlled by the Cook Islands Constitution. This document took effect on the 4th of August 1965 and every year on Constitution Day, huge celebrations are held on Raro.

Legislative power is vested in the Cook Islands Parliament. In 1946, a Legislative Council was established and empowered to legislate for the “peace, order and good government” of the islands. This Council was unable to pass laws repugnant to the laws of New Zealand, impose import and export duties, or create criminal offences with a maximum sentence greater than 1-year imprisonment. In 1957, the Legislative Council was reorganised into a Legislative Assembly which, in turn, gained full legislative power in 1965. Since then, only the Cook Islands Parliament has had the power to enact laws in the Cook Islands, including any changes to the Constitution.

Today, the Cook Islands Parliament consists of 24 MPs. Ten come from Raro, while the others represent the outer islands and various coral atolls. Interestingly, this framework creates serious political intrigue in the Cook Islands come election time. Although members of Parliament are elected by universal suffrage, many commentators question whether the Legislative Assembly is actually representative of the entire Cook Islands population.

Take for instance the atoll of Rakahanga which has a population of 83 people that are represented in Parliament by one MP. In comparison, each electorate on Raro has well over 1000 electors. Thus, the vote of Cook Islanders living on Rakahanga is, statistically speaking, much more powerful than the vote of someone in Raro.

The House of Ariki is a parliamentary body that advises the Legislative Assembly on matters of land ownership and native custom. It is composed of Cook Islander high chiefs that are appointed by the King’s Representative. This body is purely advisory and can only discuss matters put to it by the Legislative Assembly.

The Cook Islands Government and Parliament are independent of the courts. The judicial process begins in the Cook Island High Court which is split into three divisions: civil, criminal and land. Most cases are presided over by Justices of the Peace but, for serious matters, judges are flown in from New Zealand. If you’re unhappy with the outcome of your case in the High Court, there is a Court of Appeal and, in certain circumstances, a matter can be elevated to the Privy Council in the United Kingdom.

Finally, the Cook Islands Constitution protects fundamental human rights including the right to life, liberty, and security; equality before the law; and the right to own property. It also protects freedom of thought, religion, speech, peaceful assembly, and association. These rights and freedoms ensure that Cook Islanders are not subject to arbitrary detention or unwarranted punishment. It also ensures that people are innocent until proven guilty through a fair hearing.

The protection of rights and freedoms in the Cook Islands Constitution is unique when compared to its larger Pacific neighbours. Australia does not expressly protect human rights in its Constitution and New Zealand, like the United Kingdom, has an uncodified Constitution. However, the protection of rights and freedoms does feature in the Constitutions of the Cook Islands’ smaller neighbours such as Fiji, Kiribati, and Tonga.

Torts and Contracts

Commercial dealings in the Cook Islands are less frequent and less complex than in Australia. A lot of people live off the land. What’s more, Cook Islanders appear to have a strong culture of “I help you, and one day you’ll help me”; or “you’ve done me wrong but, if you do me this favour, I’ll forgive you”. In this way, many Cook Islanders do away with the need for claims in tort or contract.

But never fear, the Cook Islands is still an exciting destination for enthusiasts of tort and contract law. If you’re looking for a Thornton v Shoelane ‘ticket case’ fix, buses on Raro operate in two directions—clockwise and anticlockwise. And, not unlike the facts in Australian Safeway Stores v Zaluzna, the floor of Wigmore’s Store (a local supermarket affectionately known as Wiggie’s) was occasionally slippery when we went to buy $2 ice-creams each evening.

International Law

The Cook Islands is a self-governing state in a ‘free association’ with former colonial power New Zealand. But what does this mean? Is the Cook Islands an independent country or not?

In 1962, the government of New Zealand asked the Cook Islands Parliament to decide between four options:

- Independence from New Zealand,

- Self-government,

- Integration into New Zealand, or

- Integration into a larger Polynesian federation.

The Parliament voted for Option B—self-governance without independence. As a result, the Cook Islands became politically independent but remained under New Zealand sovereignty.

This relationship is notably different to other ‘free association’ relationships in the Pacific. In places such as the Marshall Islands and Palau (which are in free association with the United States), islanders are generally only citizens of their home country but can enter the United States at any time without a visa. In contrast, all Cook Islanders automatically have both Cook Islands citizenship and New Zealand citizenship (along with all its privileges such as entry into Australia).

Under international law, there are generally four requirements that a nation must meet in order to be recognised as a state under international law. These are (1) a permanent population, (2) a defined territory, (3) government, and (4) the capacity to enter relations with other countries, with complete legal independence from other states.

The Cook Islands undeniably meets the first three criteria. The population of the islands was just over 18,000 in 2016 (with 13,000 people living on Raro). There are 15 major islands, spread over 2 million square kilometres, creating a massive Exclusive Economic Zone. As above, Cook Islanders are represented by a democratic government.

The fourth requirement is more contentious. On one hand, the Cook Islands appears to have the capacity to enter relations with other countries. In 1998, New Zealand declared before the United Nations that the Cook Islands has the competence to enter international relations ‘in its own right’. A note prepared by the Solicitor-General of the Cook Islands in 1994 refers to an ‘unbroken practice’ that the Cook Islands will only participate in New Zealand treaty action with the consent of the Cook Islands government.

On the other hand, the Cook Islands does not have sovereignty. The country remains at least nominally dependent on New Zealand and is not a member of the United Nations. Although Article 46 of the Cook Islands Constitution provides that New Zealand has no power to pass laws for the Cook Islands without consent, New Zealand has also stated that due to its long-lasting friendship with the Cook Islands, it ‘cannot repudiate the ultimate responsibility for questions of external affairs and defence’. Basically, so long as the Cook Islands chooses to not be responsible for its international affairs, New Zealand remains responsible for the islands’ foreign relations and defence.

If New Zealand is responsible for the Cook Islands’ foreign relations and all Cook Islanders have New Zealand citizenship, can we really say that the Cook Islands meets the fourth requirement? Perhaps not.

However, since my return home, the Cook Islands have moved closer to meeting the requirement, with evidence suggesting that arenow more responsible for their international affairs. In September 2022, President Joe Biden announced the United States recognises the Cook Islands as a sovereign state. In October, Australia signed the ‘Oa Tumanava partnership with the Cook Islands and one of the foundational principles of this agreement was to ‘respect each other as sovereignstates’. In December, New Zealand indicated it was prepared to support the Cook Islands with a bid to join the United Nations. This support is welcome but not strictly necessary. Under Article 41 of the Cook Islands Constitution, the islands have a right to move to full independence via a unilateral act. That is, if the Cook Islands wish to become independent, New Zealand is unable to stop them.

But full independence for the Cook Islands may come at a price. Under the current arrangement with New Zealand, Cook Islanders are free to exercise internal self-determination through politics, the economy, society, and culture, while also receiving New Zealand citizenship, access to Australia and other advantages (such as an extremely efficient COVID-19 vaccination roll-out). Benefits like these would likely be restricted if the Cook Islands became independent.

Discussions of independence also come at a time when the Cook Islands are gradually acquiring political leverage in the region. For example, the islands receive patronage from both Australia and China. On face value, the Morrison government’s Pacific Step-up program was designed to ‘forge friendships with our Pacific family’. In reality, its purpose was to ensure the Cook Islands and other islands resist Chinese influence.

For the most part, the Cook Islands government can freely decide whether it wants to improve or restrict its friendship with either Australia or China. In Raro, the debate is not just about dollars, but also about the quality of infrastructure that is delivered by each of these rival powers.

Land Law

Ownership of land is incredibly important to Cook Islanders. Not only is land a source of family pride, but without it, islanders are unable to generate income through the planting and selling of crops.

Unlike on other Pacific islands, foreigners cannot own land in the Cook Islands. That is, all land in the Cook Islands is owned by Cook Islanders. The only option for foreigners to acquire land is to sign leases for a fixed period (usually 50 to 60 years). Once these leases expire, the land goes back to traditional owners.

The land court in the Cook Islands Ministry of Justice sits every day of the week and Justices of the Peace are kept incredibly busy hearing land cases from the many families on the island. This is because, within extended family groups, land agreements are incredibly complex. Cook Islander parents divide their land between their children, who then divide land between their children, and so on. In this way, areas of land ownership in the Cook Islands keep getting smaller, and disputes become more frequent. What’s more, 95% of landowners in the Cook Islands have moved overseas—making disputes difficult to resolve.

One afternoon, I was sitting by the lagoon with Uncle Reuben, another lawyer on Raro. When I asked about land law, he started talking about ‘quick adoptions’ which is when infants are informally passed between families at birth. He told stories about people standing up in court to make a bloodline land title claim, before making the shocking discovery before the judge that they were, in fact, adopted! It seems that land agreements in the Cook Islands are less about ‘who owns where’, and perhaps more about ‘who owns who’.

Bloodlines and leases are not the only types of land agreements in the Cook Islands. If the community accepts that a person has lived and worked on the land, they may be entitled to the land through native custom. The difficulty with these types of claims is that there is no clear definition of native custom. Specifically, how long must a situation exist before it can be regarded as custom? In the United Kingdom, the general timeframe is 100 years. In the Cook Islands, the current practice is to use a ‘moving target’ specific to each claim.

The Cook Islands also face a myriad of issues associated with legal pluralism. When should the court try to resolve the uncertainties surrounding native custom? How does custom differ across the fifteen islands? Should the government invest in registers that codify native customs on each island?

Conclusions

As an undergraduate, I am just beginning to understand the different ways in which the law operates around the world. I’m sure that if I visited the Cook Islands at the end of my degree my reflections on Raro would be very different. Similarly, after staying in the Cook Islands for only two weeks, I know I have only just begun to understand the nature of the Cook Islands’ legal system. It is inevitable that I still have misconceptions about the Cook Islander way of life.

But what I know for certain is that daily life in the Cook Islands revolves around families, the land, the ocean, and religion. This relatively simple way of life requires simple rules of law that are both easy to understand and easy to enforce.

Looking back, I think this is the reason why I was drawn so quickly into the world of Cook Island law. It was refreshing to see the law operating on such a local scale—a legal system that, at least from my point of view, is responsive to the immediate, real needs of the people.

Thank you to the Short family for their generous hospitality during my stay in the Cook Islands… and for the many games of 500.