Share This Article

While we reluctantly settle back into the dreary university grind, the dining hall continues to provide a source of comic relief as we are temporarily teleported back to sunnier holiday paradises.

Stories by those fortunate enough to have been abroad to #sailcroatia or #europe2k19 leave us hysterical or choking on chicken à la king with disbelief. Some favourites include Liam Hughes cage dancing in Croatia or Hugh Beith’s environmentally-friendly Lime e-Scooter adventure across east Europe.

While some are incredibly lucky to come back with laughs and memories (Instagram pictures that will inevitably resurface on my feed weeks from now), the local residents of these beautiful destinations are increasingly experiencing a vastly different world.

Take a few steps away from the bars of Santorini and enter the bustling, everyday lives of Greek citizens. Or Turkish. Or Italian. Or British. Or Brazilian. Or American.

You will find a common story — a pulsating sense of discontent, disenfranchisement and activism, which threatens to undermine ruling establishments.

This is a story of the average Joes and Jills of the world, their fight for perceived fairness and why their actions constitute a fundamental yet thorny issue of democratic fabric.

The story I am referencing is, of course, populism.

The popular populist label

Populism has been around for a while. We celebrate key historical populist events every year. On 14 July, masses of people flood the Champs-Élysées and gaze over a formidable display of lethal military force. They picnic on the Champ de Mars with delectable grazing platters underneath a dazzling fireworks display, erupting from the Eiffel Tower. You might have been one of them.

Fast forward two hundred and thirty years from the Storming of the Bastille and we find ourselves in the midst of another wave of French populism, climaxing in the Yellow Vest movement.

Despite our extensive and historical relationship with populism, there has recently been widespread mischaracterisation of the word in public discourse.

Populism, noun

‘A political approach that strives to appeal to ordinary people who feel that their concerns are disregarded by established elite groups’

– Oxford English Dictionary

At its classic academic core, populism consists of two key ideas: firstly, society can be divided into the good ordinary people and a nefarious establishment of politicians and institutions; secondly, that the purpose of politics is to represent the unanimous voice of the people.

As of recent, however, political commentators have thrown the term around to describe Trump, Brexit, Jeremy Corbyn, Rodrigo Duterte, and hardline policies on immigration and crime. The New York Times even claimed after this year’s federal election: “Scott Morrison … scored a surprise victory… propelled by a populist wave.”[1] Its widespread use is particularly pertinent in Europe, where it is often incorrectly conflated with nativism or nationalism.

Some posit the notion that because such a smattering of political ideologies can be classified under the populist umbrella, the term almost becomes obsolete. I tend to disagree.

To understand the relevance of populism in our time, we must then reconcile these two contexts in which populism is used. The resulting concept is that populism is not an ideology in and of itself. Rather, it is a vehicle through which various ideologies can be expressed.

This distinction is crucial and being able to recognise populism for what it is, a political style to express various ideologies, is now more relevant for our democracy than ever before.

Populism as a facade

The reason why populism can be used to describe candidates and supporters from across the political spectrum is because it facilitates a fundamental truth of democracy as we know it — the political status quo is only ever temporary and should be representative of what voters believe at that point in time. Therefore, when a candidate declares themselves as a populist, they are proclaiming that they represent the voice of ‘us’, the people, and anyone who disagrees with their ideology must be pitted against them.

It is easy to see why people flock to such an agile term. Because populism does not hinge itself to a particular set of values or ideals, it is easy (and lazy) to accept the term at face value and assume that all populist movements are in the best interests of every citizen. The populist label makes ideologies and policies secondary because if these candidates are representing the people, and if we believe in liberal democracy, then surely they are deserving of office. Obviously, this logic does not hold.

To see why, let us consider two examples.

The recent use and acceleration of the populist label was borne out of Europe in the 1990s where right-wing nativism and racist sentiments in countries including Italy, Denmark and Switzerland were on the rise. Parties which identified as right-wing typically had anti-immigration policies and claimed that their country should be returned to their ethnically ‘pure’ citizens. Right-wing inspired violence was also prevalent during this decade.

It was during this political climate that right-wing parties started to identify as populist, representing the views of the ‘real’ people. This facade was a powerful tool in deflecting the criticism of their nativist mantra and presented a more appealing label than ‘right-wing extremists’.

For a more current example, take Trump. We are all too familiar with his rambling and tangential tendencies. However, when he does stay on script, his speechwriters skilfully lace his material with populist rhetoric and he adopts a vastly different demeanour. He suddenly becomes a champion for the people.

In his inauguration speech, he said, “For too long, a small group in our nation’s Capital has reaped the rewards of government while the people have borne the cost…The establishment protected itself, but not the citizens of our country.”

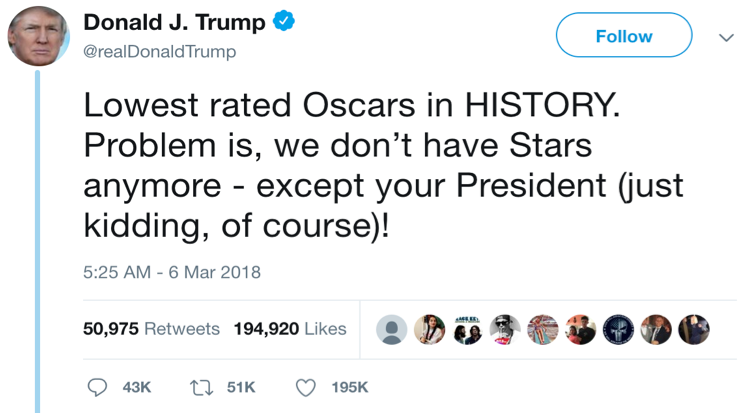

In contrast, I think of Trump as a narcissist. In his own words, he’s a “Star”. Capitalised!

He even once mistook the term and allegedly said to Steve Bannon, former White House Chief Strategist, “That’s what I am, a popularist.”[2]

Such an approach seems out of character. Not the incessant tweets nor the fictitious words. His populist facade.

Populism is propelled by multiple sources of discontent

Just because populism is often considered to have detrimental democratic effects does not necessarily mean that the reasons why populist movements are brought about in the first place are illegitimate.

I think of the drivers of populism as threefold:

Firstly, sluggish wage growth and increasing globalisation have left people behind economically. Despite coming across the same statistic many times, it still surprises me that the world’s 26 richest people own as much as the poorest 50%[3]. Even in countries where wage growth has kept up with or exceeded inflation, it is the feeling of perceived inequality and relative, not absolute, deprivation which drives populist rhetoric.

Secondly, many ethnic groups are still grappling with the effects of modern mass migration. Most societies in Europe were founded on a mono-ethnic basis and so the modern pluralist culture becomes an easy scapegoat for issues such as job security. Even the USA, which was founded by immigrants and was always multi-ethnic, still retained an ethnic hierarchy which arguably exists in pockets today and continues to drive anti-immigration rhetoric of the vocal minority.

Finally, the creation of social media platforms has enabled these originally fringe and disparate sentiments to amalgamate into an unprecedented and unified global voice. Tools that were originally designed to bring people together in a collaborative environment now contribute to the echo chambers of individual beliefs.

Whilst populism may result from these drivers, it often does not provide a comprehensive answer to the problems it seeks to address. Globalisation, mass migration and social media regulation are all complex topics with a myriad of effects too convoluted for any one political style to tackle satisfactorily.

A challenge of our commitment to liberal democracy

I hazard a guess that the majority of current St Andrew’s College residents have not experienced a form of governance other than liberal democracy throughout our lifetimes, and probably a relatively strong one at that. We tend to incorrectly assume that the impetus for civic education is becoming more unimportant because of its recent stability.

Surprisingly, a joint study between the University of Melbourne and Havard University uncovered that only 19% of American millennials agreed with the statement “military takeover is not legitimate in a democracy”[4]. More locally, Australian democratic satisfaction is at an all time low of 41% and the major party vote slumped to below 75% in this year’s federal election, the lowest since post-war times[5].

Where we find ourselves now is at the crossroads between a waning faith in mainstream politics and a rise in populist movements. The implications for democracy when a populist is in power are generally bad. Political scientists and economists have long heralded that under populist governance, press freedom is undermined, executive power is over-reached and that civil and political rights of individuals are eroded. All of this occurs whilst populist leaders last longer in power[6].

However, if you believe in the principles of liberal democracy, it is not enough to endorse or denounce populist movements at face value. Given that populism is part and parcel of the democratic process, it is your civic duty to understand the factors and ideologies behind a populist label. Is the attractive allure of an easily-relatable populist cause backed up by values and solutions that you agree with and do they provide practical solutions to society’s issues? Those are the sorts of questions we need to be asking ourselves.

If we do not engage on a deeper level with populist movements, we run the risk of weakening our democracy — future movements that may be worthwhile and legitimate can easily become undermined by a simple populist label, or vice versa. Indeed, the malleable connotations of the word ‘populist’ are dependent on what movements are now labelled as populist, how we interact with them and what their implications are.

It is easy to forget the inherent fragility of our democratic processes. It is our collective duty to re-examine our commitment to liberal democracy. If we determine that we enjoy our current system of governance, then it is up to each of us to become more nuanced and educated in the way that we discuss populism and its potential positive or negative impact on society.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/18/world/australia/election-results-scott-morrison.html

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/sep/05/bob-woodward-fear-donald-trump-steve-bannon

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jan/21/world-26-richest-people-own-as-much-as-poorest-50-per-cent-oxfam-report

[4] https://qz.com/848031/harvard-research-suggests-that-an-entire-global-generation-has-lost-faith-in-democracy/

[5] https://drewsnews.standrewscollege.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/attachments/Democracy2025-report1.pdf

[6] https://institute.global/insight/renewing-centre/populist-harm-democracy

Images: Ingo Joseph from Pexels and Twitter