Share This Article

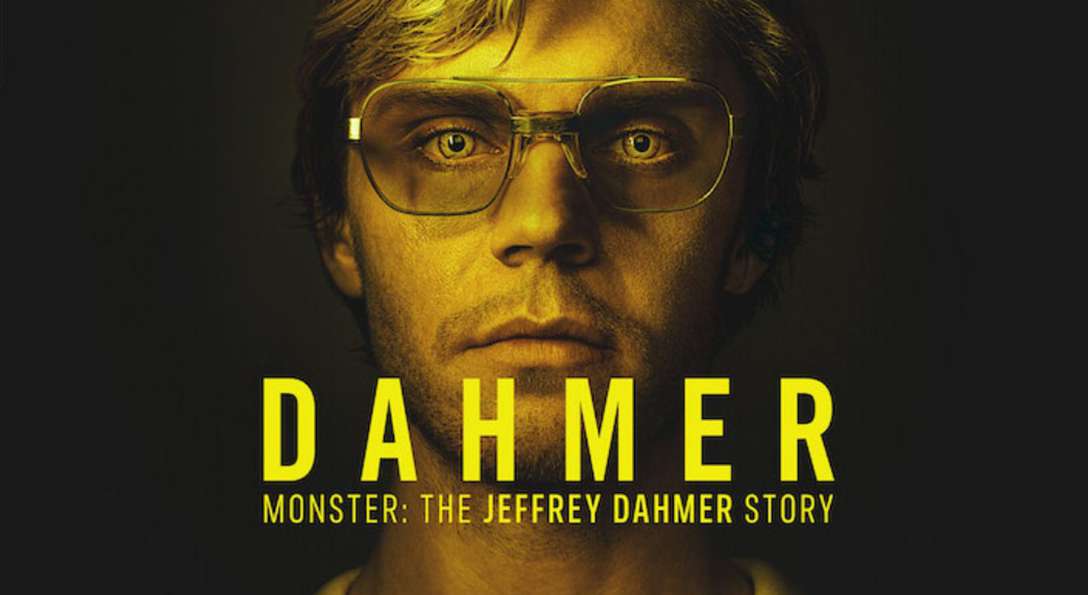

True crime is everywhere. Turn on the TV, pick a podcast, or go on social media, and you’ll find it. Of course, there is good reason for this – we all love true crime. I’ll admit it, I’m an addict, and binge-watched Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, a 10-part Netflix series looking into the life of notorious serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, in less than 3 days. And I’m sure I wasn’t alone, considering the series was watched for over 196 million hours within the first week of its release, cementing its status as the number-one show on the streaming platform at the time of publishing.

As of 2022, true crime is one of the most popular genres on Netflix, entrancing audiences with storytelling, suspense, and a collective longing for justice. From Don’t F**k With Cats, The Vanishing at the Cecil Hotel, Making a Murderer, to the Ted Bundy biopic, Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil, and Vile, we can’t seem to help but consume every ounce of this genre that Netflix loads up on our plates. Yet, while true crime is proving to be one of the fastest-growing areas of entertainment, it is also an ethical minefield.

Despite garnering record-breaking success, officially becoming one of Netflix’s most streamed shows of all time, Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story has been no stranger to controversy. After its launch, family members of Dahmer’s victims were quick to criticise Netflix for not consulting them while making the drama. Rita Isbell, whose victim impact statement was re-enacted in the series following her brother’s murder, told Insider: “I feel like Netflix should’ve asked if we mind or how we felt about making it. They didn’t ask me anything. They just did it.”. Isbell added, “But I’m not money hungry, and that’s what this show is about, Netflix trying to get paid.”.

However, from a legal standpoint, Netflix isn’t obligated to consult the victims’ families or ask their permission to make these types of shows. All public court records and footage is fair game for the entertainment industry to use without getting consent. It’s in this way that navigating the ethics of true crime is tricky… just because Netflix isn’t breaking the law by creating content out if it doesn’t make it right.

Netflix promoted the series by claiming that it “gives Jeffrey Dahmer’s victims a voice”. But according to who? True crime fans? The victims themselves? Their families? Evidently not the latter.

Critics of true crime have also emphasised the genre’s potential to cause further pain to victims’ families, especially when it comes to dramatic retellings like Monster which are predicated on hyper-realistically recreating the murders of victims in graphic detail. I mean, imagine the absolute worst torment that could ever happen to you being turned into entertainment for strangers across the world to watch with their favourite snacks and discuss at the dinner table, only to forget about it the next day. The reality for victims’ families is that they never forget what happened. The pain never goes away. And having this pain dramatised to a global audience, without their consent, probably doesn’t help.

Isbell’s cousin Eric Perry spoke out about this on Twitter, challenging viewers to consider the real people still impacted by Dahmer’s crimes in a tweet that reads: “I’m not telling anyone what to watch, I know true crime media is huge rn, but if you’re actually curious about the victims, my family (the Isbell’s) are pissed about this show.” He continues, “It’s retraumatizing over and over again, and for what? How many movies/shows/documentaries do we need?”

Perry has a point. Wikipedia lists 20 Jeffrey Dahmer projects that have been released since 1992, including 2017’s My Friend Dahmer, 2020’s Jeffrey Dahmer: Mind of a Monster, and 2012’s The Jeffrey Dahmer Files. So, do we really need more ‘awareness’ of/’insight’ into serial killers like Dahmer? Or do we need to be honest about the consequences of retelling real tragedies? After all, as Perry told the LA Times, “We’re all one traumatic event away from the worst day of your life being reduced to your neighbor’s favorite binge show.”

But the ethical question of true crime doesn’t stop here.

In addition to concerns of exploiting real-life pain and suffering for profit, many have condemned shows like Monster for sensationalising and glorifying serial killers – or at least irresponsibly enabling this fetishization. Following the series’ launch, Jeffrey Dahmer’s signature aviator glasses went up for sale for a whopping $150k, alongside several signed items such as a Thanksgiving greeting card he sent to his parents while incarcerated. A nightclub in France threw a Dahmer-themed event, while some have thought it a good idea to dress up as Dahmer for Halloween. On TikTok, the killer has become an internet sensation, with users utilising him as a source of comedy: “If Jeffrey Dahmer met an Aussie”. Evan Peters playing Dahmer in the series has also led to various compilations raving about how ‘hot’ he is.

The show, it seems, has amplified Dahmer more than ever before, renewing him a sort of ‘superstar’ status. But Jeffrey Dahmer is no Justin Bieber. Lest we forget, he was a serial killer, paedophile, necrophiliac, and cannibal who murdered and dismembered 17 people. And while I would not go as far to say that Netflix’s Monster intended to romanticise this man, the risk of true crime drama inadvertently glamourising notorious serial killers, and erasing their victims with the coverage, is a real one.

This unwanted by-product is nothing new, with a similar reaction occurring following the 2019 release of the Ted Bundy biopic starring Zac Efron. The influx of tweets discussing Bundy’s attractiveness escalated to the point that Netflix had to beg its viewers to stop. Again, like Dahmer, Bundy was a serial killer who tortured, raped, and murdered dozens of people, and whose victims’ families are also very much still alive.

The danger of fictionalising and dramatising serial killers is that rather than driving understanding and awareness, scripted productions like Monster make it easier to lose sight of the fact that true crime is not just entertainment. They are real stories about real people, with real families and real lives that were cruelly cut short. And the ugly truth of true crime is that it comes with very real consequences.

Yes, ethics in true crime are a grey area. But it’s clear that companies like Netflix need to do better to care for victims’ families instead of putting aside their interests for the larger good of serving the audience. Many have suggested reaching out to families and asking for their permission, or giving some profits to charities or foundations launched in the victims’ names. While it may not be a legal obligation, it is certainly the right thing to do.

But where does that leave us as viewers? Can we blame streaming platforms for continuing to make these films and shows if we’re so consistently tuning in to watch them? It takes two to tango. So, has our obsession with trauma porn finally gone too far?

I’m sure none of us watch true crime with the intent to cause harm, and ultimately, there will always be an audience for stories of the murderous and macabre, with fascination in the darker side of life an incredibly common human impulse. But perhaps it’s time we start asking ourselves if that alone justifies perpetuating the exploitation cycle – particularly when it comes to shows that lean towards a stylised narrative and veer away from educational value. Sure, streaming platforms need to be asking the same questions of their content, but attention is currency in the entertainment world.

Nevertheless, the debate surrounding how and when to tell tragic stories will continue, and although I’m tentative to say that I’ve put my true crime days behind me, I do think there is value in conscious consumption. In light of Netflix announcing it will be going ahead with two more seasons of Monster, as viewers, that means engaging with and amplifying the voices of surviving families, it means evaluating what you’re watching and more importantly, why.