Share This Article

Nina Friars reflects on her heritage and her story in an emotional and poignant letter to her friends for the Drew’s News Lockdown Writing Competition.

“Cradled in one culture, sandwiched between two cultures, straddling all three cultures and their value systems, undergoes a struggle of flesh, a struggle of borders, an inner war.” – Gloria Anzaldúa

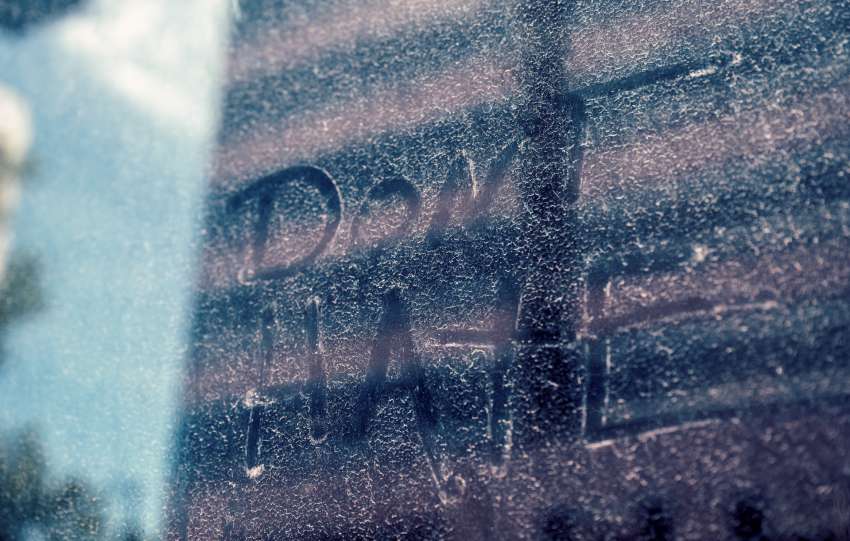

I came across this quote earlier this year in my studies. It has resonated with me ever since. I find it has a certain poetry to it and puts my feelings about being mixed-race, as half white and half Anglo-Indian, into words. I am writing this letter to tell you more about the lived experience of biracial identities as well as the ways in which I have come to suffer this “inner war”. By sharing insight into my internal conflicts, I hope you begin to appreciate the struggles that come with being mixed-race and recognise how we share familiarities with racialized identities, but also uniquely diverge from them.

As a child, I was completely unaware of my own racial identity. While I was accustomed to white teachers, family members, shop clerks and even my mother expressing their envy of my ‘olive skin tone’, I merely perceived myself as ‘tan’ and my Anglo-Indian father as considerably more ‘tan’ than myself. I simply did not know I was mixed-race – let alone non-white. How could I have known? Being mixed-race, or any race for that matter, is not a natural categorisation understood innately. It is not an essence nor something fixed, concrete and objective. Rather, race is an element of social structure realised through the perceptions of others.

It was not until I was racialized that I discovered my mixed-race identity. Despite being born and raised in Australia, my adolescence was plagued with puzzled white Australians asking, “Where are you really from?”, which always felt like another way of saying, “You aren’t white, but you aren’t brown. What are you?”. Whether it be on the street, at the restaurant I worked at or in the queue at my local grocery store, such a line of questioning forced an awareness of my difference; a difference indelibly marked on my body. I was clearly not white enough to claim belonging in Australia. To my dismay, this lack of belonging followed me to India as well where amongst my father’s family I was too white to be considered brown.

Facing rejection from both racial groups I am part of as I could not be classified in either has led to my understanding that society cannot provide answers for biracial identities in the same way it has for those who are monoracial. For monoracial individuals, racial categorisation is pretty straightforward: A stranger approaches you, they categorise you and you know intuitively what category that is. However, it is not that simple for mixed-race identities. I have come to recognise that society’s conceptualisation of race fails to work for biracial bodies like my own as our difference is difficult to discern. Realising this, it’s no wonder that people incessantly question my ethnicity as their inquisitiveness is reflective of their confusion, their inability to easily place my body within the racial binary.

While I have been a victim of “Othering”, my racial ambiguity has afforded me White-passing privileges that non-White-passing People of Colour do not have access to. Within my lifetime so far, there have been countless times where I have been assumed as white. I have had girls ask me what brand of fake tan I use as if I was not born this colour. I have met people who respond with utter disbelief once they discover my ethnicity, replying with the likes of, “There’s no way you’re Indian! You look white.” Although these encounters trigger an inner turmoil in their delegitimization of the Anglo-Indian parts of me, I am unequivocally aware that my White-passing abilities allow me to benefit from White privilege. I acknowledge that my experiences of race and inequality are wholly incomparable to non-White-passing People of Colour like my father as I still have unearned assets I can count on cashing in each day.

As no-one discussed my mixed-race identity, I thought I needed to choose between racial identities to fit into society’s binaries and feel validated. White privilege was recognisable to me from a young age, so it was a no brainer to actively seek proximity to Whiteness. I realised through my mother that Whiteness afforded one with access, acceptance and belonging. I found myself envious of the way in which she seamlessly blended into Australia’s national identity in all her blonde hair, blue-eyed, stereotypical glory.

Contrastingly, my father threatened my desire for Whiteness. I remember feeling embarrassed and ashamed of his presence in primary school because I feared he might jeopardise my ability to pass as white, standing out as a fierce indicator to others that I am in fact a Person of Colour and not just ‘that tan girl’. It was my mother who I wanted to watch my soccer games and pick me up from school. I felt comfortable by her side as I thought that in being near her, I could be seen as White too and have a share in its privileges. I learnt to hide my ethnic identity by refusing to take my Anglo-Indian lunches to school, opting for my mother’s sandwiches in a bid to assimilate to White Australian culture.

To this day, I still struggle with taking pride in my Anglo-Indianness and shamefully catch myself falling victim to internalized racism. For example, I have found that I often manipulate my appearance in certain ways so I can appear ‘Whiter’. I typically gravitate towards clothes and makeup that emphasize my lighter-coloured eyes as I believe this feature anchors me to Whiteness. I’ve even considered dying my dark brown hair blonde in the hopes I may look less ethnic and perhaps be considered more attractive in conforming to White, Western beauty standards. While reflecting on the ways in which I suffer from internalised racism brings me deep humiliation and is something I am still in the process of unlearning, I nonetheless believe that this conditioning of mixed-race identities to value the Whiter, more privileged facets of our identities is an important reality that cannot be overlooked.

As a mixed-race woman, my experiences have led to the discovery that our bodies are often exotified and fetishized. I think I was around fourteen the first time I was described as ‘exotic’ by a White man. Initially, I believed that such comments were flattering as I equated the word ‘exotic’ with being beautiful, unique and captivating. However, as I have grown older, I have come to learn that the term ‘exotic’ means something quite different. In its implication that I am non-conventional to the environment, I have realised that being described as exotic is a form of Othering; a way of highlighting my body as deviant to the norm of Whiteness.

One scroll through my Tinder messages and the ways in which men exoticize biracial identities is extremely apparent: “Those eyes and that skin! There’s no way you’re from around here.” or “Wow! You have such an exotic look.”. Despite their intention to express a compliment, I am immediately reminded of my difference, that I am perceived as a foreigner in my own birthplace, that I fail to meet the dominant narrative of beauty. It leaves me feeling objectified, dehumanized and fetishized as if my only distinguishable value is my ethnicity, subsequently placing it above who I am as a person. It makes me deliberate whether these men find me attractive in spite of my biracial identity or because of it. It leaves me wondering if I were a couple shades darker like my father, if such men would still find me attractive or if my ‘exotic beauty’ is due to my possession of just the right amount of ethnic ambiguity.

As biracial, I also grapple with comprehending my position to speak on issues of race as someone who possesses White-passing privileges but has also been on the receiving end of racially charged prejudice. If I am assumed as White in some contexts but Brown in others, what does this mean in terms of the validity of my voice when discussing racism? I felt this struggle at an anti-racist workshop at college which addressed microaggressions that I am – unfortunately – more than familiar with. I found myself hesitate before contributing to discussion as I speculated whether my peers saw me as White or non-White and how either identity would influence the gravity of what I had to say. On one hand, I wanted to express the privilege of my Whiteness, and on the other, I wanted to communicate the oppression of my Anglo-Indianness. Yet, my racial ambiguity means that talking on behalf of either race I am part of is problematic as I cannot fully comprehend their distinct experiences. It is because of this membership in conflicting racial groups that mixed-race individuals face extraordinary challenges in locating their position in racial discourse.

Ultimately, biracial bodies overlap and depart from experiences of racialized bodies. My mixed-race experiences are not black and white just as I am neither black nor white. Although there is a lot left unanswered, I am grateful I now have the tools to embrace my identity instead of battle with it. I am grateful I finally have the vocabulary to articulate my biracial experiences to you in this letter.

I hope that through sharing my personal thoughts and insights, you realise how mixed-race bodies straddle multiple worlds; “a struggle of flesh, a struggle of borders, an inner war”, and in recognising this, you will reflect before saying things that may exacerbate their struggle. I hope you come to understand and appreciate my position on mixed-race identities in that although our existence shares similarities with racialized bodies, we also have experiences that are fiercely unique, experiences that are our own. I hope this letter encourages you to think outside of the black/white racial binary and that you realise how such binaries ground our everyday interactions.

But mostly, I hope you believe me when I say that biracial identities are worth talking about, that our experiences matter and people need to know what it’s like to be us. Society is undoubtedly ill-equipped to discuss mixed-race and this desperately needs to change. We need to be seen, we need to be heard, but for now, if you are listening to and acknowledging my experiences, we are one step closer.

Yours sincerely,

Nina

This piece won the Drew’s News Lockdown Writing Competition 2021.

Image: Pexels