Share This Article

George Bright analyses the psychology behind football and the effect on Australia’s football culture.

Since the apogee of the Socceroos at the 2015 Asian Cup, Australia’s progress towards consistently becoming genuine contenders at the international level has seemingly stagnated. After unforgettably qualifying for the 2006 World Cup at expense of Uruguay, 13 of Australia’s 23 man playing squad were participating in one of Europe’s top 4 leagues. By 2018 that number had dropped to just three in Mat Ryan, Aaron Mooy and Matt Leckie. So, what has changed? There are, of course, countless factors that contribute to success in sport and the influence of chance should not be discredited. Short of striking the generational talent jackpot though, what is it that distinguishes that cohort from our current crop of stars on the pitch? One component of the answer may be best exemplified by a small club from rural Denmark, FC Midtjylland.

FC Midtjylland are probably most remembered for their 2-1 thrashing of Manchester United in the 2016 Europa League round of 32 (though they were eventually defeated 6-3 on aggregate). For close observers though, their presence in the competition was noteworthy even in itself. After being founded in 1999, the young club have made a name for themselves through their analytics-based approach to football which paid dividends after they won their first title in 2015. It is their unique personality test though that may help to explain Australia’s current decline.

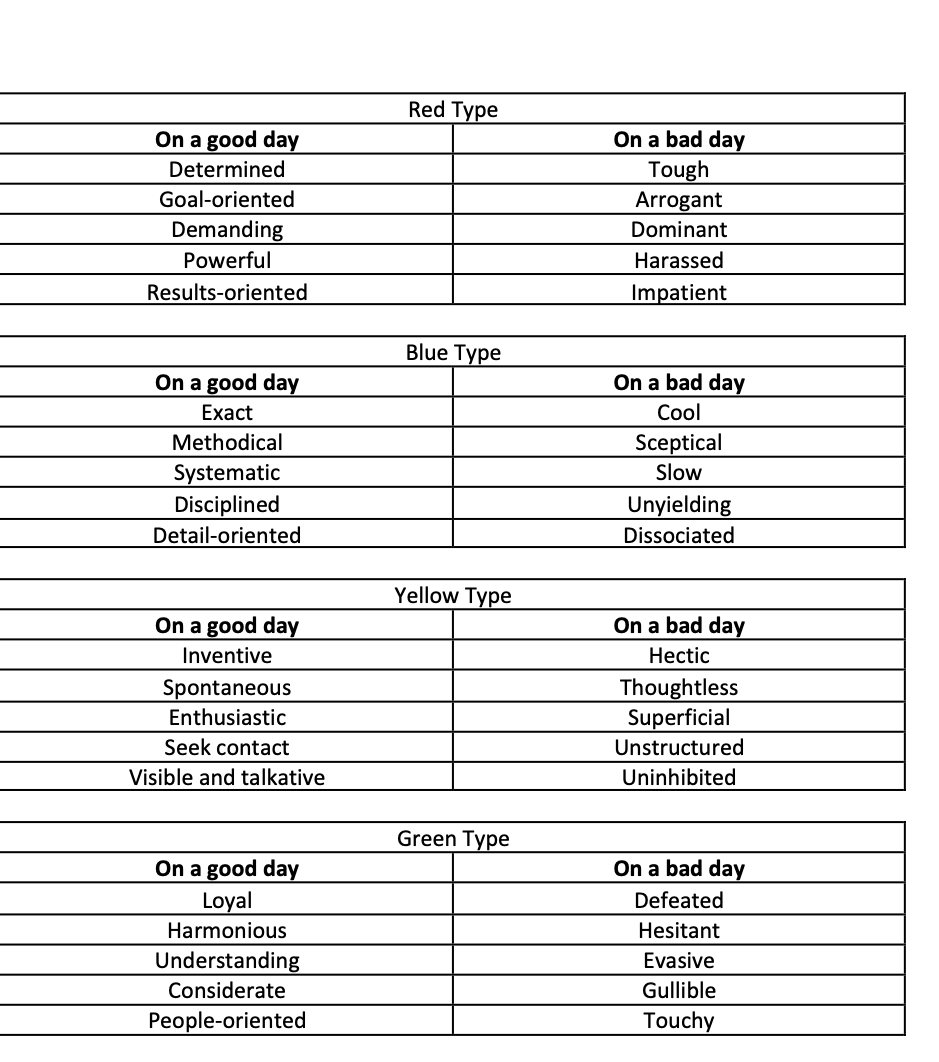

Although often maligned, personality tests of one description or another are commonplace among many top clubs in world football. FC Midtjylland’s tests, delivered to all staff and players, score participants into four broad categories giving them an overall direction as to which one they best fit into. The four categories are simply titled Red, Blue, Green and Yellow. Of course, everyone has some blend of each, there is no one who fits solely in one category. The test is designed to be used as a descriptive measure rather than a pigeon-hole perspective of a person. It gives players a better understanding of both their own and their teammates tendencies and communication styles, allowing players to recognise potential strengths and weaknesses associated with their character. Senior player Tim Sparv describes this in an interview with thesetpieces.com reflecting that “the blue colour is someone who is very systematic, very disciplined, a reflective person … the more negative side is that [the blue personality] is a little bit unapproachable. On a bad day he can be a bit stubborn, a bit sceptical”.

(Extracted from Christoph Biermann’s excellent Football Hackers: The Science and Art of a Data Revolution)

When assessing why Australia is not excelling as a footballing nation a few things become immediately clear. Firstly, Australians are not physically outmatched. There is no suggestion that fitness, speed or strength are qualities lacked by Australian players and with access to some of the best strength and conditioning coaches and facilities in the world, along with ever continuing improvements in the field, the source of our underperformance must be found elsewhere.

The next obvious point is that although football is not at the forefront of most Australian sporting fans minds, the pool of selection is far from shallow. Australia’s pathways to elite performance may be flawed (a topic which may be explored another day) but there are still over half a million registered outdoor football players in Australia, with the FFA estimating a total of 1.8 million people participating in football in some capacity. Comparatively, that’s roughly the same amount of people playing football in Australia as there are men living in Uruguay.

That leaves the technical and cognitive sides of the game as the areas where Australian players could be lacking. Technically; it seems flawed to claim that players who train almost every day of the week through much of their childhood and most of their professional lives could fail to reach the same standard as their peers around the world simply due to geography. This is where FC Midtjylland’s personality test may be a useful tool to apply. Australia is producing too many “Blue” players.

Crucially, it’s not just that there are too many Blue players but that there is a dearth of creative problem solvers playing top level football. This was especially noticeable at the 2018 World Cup where Australia failed to score a single goal from open play and registered only 2.13 non-penalty xG according to InfoGol’s stats. There were some signs of encouragement though. The inclusion of Dimi Petratos in the squad was a sign that the creative playmaker has not gone extinct in the A-league and Daniel Arzani might be the brightest young talent since Harry Kewell.

Some may point to the introduction of the A-league as the point where Australia’s performance began to decline. There may be some merit in that, as the birth of the ‘golden generation’ dates back to the days of the NSL. Since the A-league’s inception a host of overseas players such as Alessandro Del Piero and Miloš Ninković have been brought in to woo crowds and seemingly shortcut our lack of creative quality domestically. Others will point to the FFA’s management of grassroots football, or the “win now” culture of youth sport. Some may even claim there is no issue with the players Australia is currently producing but they have simply lacked the right manager to get the best of them. As with most things, the truth is probably somewhere in the middle. Regardless of where you stand, it is clear Australian football needs a creative change.